The giraffe (Giraffa) is a genus of African even-toed ungulate mammals, the tallest living terrestrial animals and the largest ruminants. The genus currently consists of one species, Giraffa camelopardalis, the type species. Seven other species are extinct, prehistoric species known from fossils. Taxonomic classifications of one to eight extant giraffe species have been described, based upon research into the mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, as well as morphological measurements of Giraffa, but the IUCN currently recognizes only one species with nine subspecies.

The giraffe’s chief distinguishing characteristics are its extremely long neck and legs, its horn-like ossicones, and its distinctive coat patterns. It is classified under the familyGiraffidae, along with its closest extant relative, the okapi. Its scattered range extends from Chad in the north to South Africa in the south, and from Niger in the west to Somalia in the east. Giraffes usually inhabit savannahs and woodlands. Their food source is leaves, fruits and flowers of woody plants, primarily acacia species, which they browse at heights most other herbivores cannot reach. They may be preyed on by lions, leopards, spotted hyenas and African wild dogs. Giraffes live in herds of related females and their offspring, or bachelor herds of unrelated adult males, but are gregarious and may gather in large aggregations. Males establish social hierarchies through “necking”, which are combat bouts where the neck is used as a weapon. Dominant males gain mating access to females, which bear the sole responsibility for raising the young.

The giraffe has intrigued various cultures, both ancient and modern, for its peculiar appearance, and has often been featured in paintings, books, and cartoons. It is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as Vulnerable to extinction, and has been extirpated from many parts of its former range. Giraffes are still found in numerous national parks and game reserves but estimations as of 2016 indicate that there are approximately 97,500 members of Giraffa in the wild, with around 1,144 in captivity.

Etymology

The name “giraffe” has its earliest known origins in the Arabic word zarāfah (زرافة),[2] perhaps borrowed from the animal’s Somali name geri.[3] The Arab name is translated as “fast-walker”.[4] There were several Middle English spellings, such as jarraf, ziraph, and gerfauntz.[2] The Italian form giraffa arose in the 1590s.[2] The modern English form developed around 1600 from the French girafe.[2] “Camelopard” is an archaic English name for the giraffe deriving from the Ancient Greek for camel and leopard, referring to its camel-like shape and its leopard-like colouring.[5][6]

Taxonomy

Living giraffes were originally classified as one species by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. He gave it the binomial name Cervus camelopardalis. Morten Thrane Brünnich classified the genus Giraffa in 1772.[7] The species name camelopardalis is from Latin.[8]

Evolution

The giraffe is one of only two living genera of the family Giraffidae in the order Artiodactyla, the other being the okapi. The family was once much more extensive, with over 10 fossil genera described. Their closest known relatives are the extinct deer-like climacocerids. They, together with the family Antilocapridae (whose only extant species is the pronghorn), belong to the superfamily Giraffoidea. These animals may have evolved from the extinct family Palaeomerycidae which might also have been the ancestor of deer.[11]

The elongation of the neck appears to have started early in the giraffe lineage. Comparisons between giraffes and their ancient relatives suggest that vertebrae close to the skull lengthened earlier, followed by lengthening of vertebrae further down.[12] One early giraffid ancestor was Canthumeryx which has been dated variously to have lived 25–20 million years ago (mya), 17–15 mya or 18–14.3 mya and whose deposits have been found in Libya. This animal was medium-sized, slender and antelope-like. Giraffokeryxappeared 15 mya in the Indian subcontinent and resembled an okapi or a small giraffe, and had a longer neck and similar ossicones.[11] Giraffokeryx may have shared a clade with more massively built giraffids like Sivatherium and Bramatherium.[12]

The extinct giraffid Samotherium (middle) in comparison with the okapi (below) and giraffe. The anatomy of Samotheriumappears to have shown a transition to a giraffe-like neck.[13]

Giraffids like Palaeotragus, Shansitherium and Samotherium appeared 14 mya and lived throughout Africa and Eurasia. These animals had bare ossicones and small cranial sinuses and were longer with broader skulls.[11][12] Paleotragus resembled the okapi and may have been its ancestor.[11] Others find that the okapi lineage diverged earlier, before Giraffokeryx.[12] Samotherium was a particularly important transitional fossil in the giraffe lineage as its cervical vertebrae was intermediate in length and structure between a modern giraffe and an okapi, and was more vertical than the okapi’s.[13] Bohlinia, which first appeared in southeastern Europe and lived 9–7 mya was likely a direct ancestor of the giraffe. Bohlinia closely resembled modern giraffes, having a long neck and legs and similar ossicones and dentition.[11]

Bohlinia entered China and northern India in response to climate change. From there, the genus Giraffa evolved and, around 7 mya, entered Africa.[14] Further climate changes caused the extinction of the Asian giraffes, while the African giraffes survived and radiated into several new species. Living giraffes appear to have arisen around 1 mya in eastern Africa during the Pleistocene.[11] Some biologists suggest the modern giraffes descended from G. jumae;[15] others find G. gracilis a more likely candidate.[11] G. jumae was larger and more heavily built while G. gracilis was smaller and more lightly built. The main driver for the evolution of the giraffes is believed to have been the changes from extensive forests to more open habitats, which began 8 mya.[11] During this time, tropical plants disappeared and were replaced by arid C4 plants, and a dry savannah emerged across eastern and northern Africa and western India.[16][17] Some researchers have hypothesised that this new habitat coupled with a different diet, including acacia species, may have exposed giraffe ancestors to toxins that caused higher mutation rates and a higher rate of evolution.[18] The coat patterns of modern giraffes may also have coincided with these habitat changes. Asian giraffes are hypothesised to have had more okapi-like colourations.[11]

In the early 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck believed the giraffe’s long neck was an “acquired characteristic”, developed as generations of ancestral giraffes strove to reach the leaves of tall trees.[19] This theory was eventually rejected, and scientists now believe the giraffe’s neck arose through Darwinian natural selection—that ancestral giraffes with long necks thereby had a competitive feeding advantage (competing browsers hypothesis)[20] that better enabled them to survive and reproduce to pass on their genes.[19]

The giraffe genome is around 2.9 billion base pairs in length compared to the 3.3 billion base pairs of the okapi. Of the proteins in giraffe and okapi genes, 19.4% are identical. The two species are equally distantly related to cattle, suggesting the giraffe’s unique characteristics are not because of faster evolution. The divergence of giraffe and okapi lineages dates to around 11.5 mya. A small group of regulatory genes in the giraffe appear to be responsible for the animal’s stature and associated circulatory adaptations.[21]

Species and subspecies

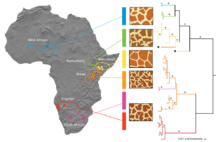

“Approximate geographic ranges, fur patterns, and phylogeneticrelationships between some giraffe subspecies based on mitochondrial DNA sequences. Colored dots on the map represent sampling localities. The phylogenetic tree is a maximum-likelihood phylogram based on samples from 266 giraffes. Asterisks along branches correspond to nodevalues of more than 90% bootstrapsupport. Stars at branch tips identify paraphyletic haplotypes found in Maasai and reticulated giraffes”.[22]

The IUCN currently recognizes only one species of giraffe with nine subspecies.[23][24] In 2001, a two-species taxonomy was proposed.[25] A 2007 study on the genetics of Giraffa, suggested they were six species: the West African, Rothschild’s, reticulated, Masai, Angolan, and South African giraffe.[22] The study deduced from genetic differences in nuclearand mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that giraffes from these populations are reproductively isolated and rarely interbreed, though no natural obstacles block their mutual access. This includes adjacent populations of Rothschild’s, reticulated, and Masai giraffes. The Masai giraffe was also suggested to consist of possibly two species separated by the Rift Valley.[22]

Reticulated and Masai giraffes have the highest mtDNA diversity, which is consistent with giraffes originating in eastern Africa. Populations further north are more closely related to the former, while those to the south are more related to the latter. Giraffes appear to select mates of the same coat type, which are imprinted on them as calves.[22] The implications of these findings for the conservation of giraffes were summarised by David Brown, lead author of the study, who told BBC News: “Lumping all giraffes into one species obscures the reality that some kinds of giraffe are on the brink. Some of these populations number only a few hundred individuals and need immediate protection.”[26]

A 2011 study using detailed analyses of the morphology of giraffes, and application of the phylogenetic species concept, described eight species of living giraffes.[27] The eight species are: G. angolensis, G.antiquorum, G. camelopardalis, G. giraffa, G. peralta, G. reticulata, G. thornicrofti, and G. tippelskirchi.

A 2016 study also concluded that living giraffes consist of multiple species.[28] The researchers suggested the existence of four species, which have not exchanged genetic information between each other for 1 million to 2 million years. Those four species are the northern giraffe (G. camelopardalis), southern giraffe (G. giraffa), reticulated giraffe (G. reticulata), and Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi).[28] Since then, a response to this publication has been published, highlighting seven problems in data interpretation, and concludes “the conclusions should not be accepted unconditionally”.[29]

There are an estimated 90,000 individuals of Giraffa in the wild, with 1,144 currently in captivity.